Castle beginnings

22 May 2020

Over many centuries, Edinburgh Castle has witnessed royal ceremonies, the birth of a king and the deaths of queens, devout prayers and intensive military activity.

As the castles fascinating history is so vast, let us take you on a two part tour of the castle through the years and look at the many key moments that have shaped its history.

In this part of the blog we will tell the story from the castles beginnings through to the Renaissance period that saw it flourish. Then in part two we will look at how it grew and developed in the 18th century as a military fortress up until the castle we all know and recognise today.

Where it all began…

This settlement on Castle Rock has towered above the city since the Bronze Age. Iron Age people built an extensive settlement on the rock and cut defensive ditches. In the 7th century AD it is the location of Din Eidyn, stronghold of Mynyddog ‘the Magnificent’, warlord of the Gododdin before it was seized by the Northumbrians later in the century and renamed Edinburgh.

The oldest building in the castle and the city

The first reference that we have to there being a castle on the rock is in the 11th century during the reign of Malcolm III. The castle buildings and its defences during this time are likely to have been built of timber and nothing survives of the early castle. In 1093 Malcolm’s widow, Queen (later Saint) Margaret, died whilst in residence at the Castle. Her son David I built the tiny St Margaret’s Chapel to commemorate her. It was one of the first stone buildings in the castle and remains both the oldest building in the castle and in the whole of Edinburgh.

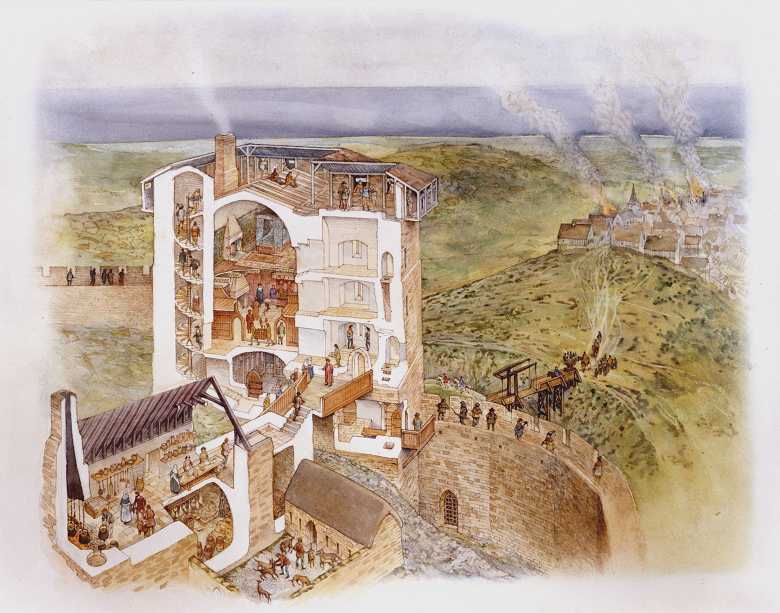

This was the only building left standing in 1314 when King Robert the Bruce ordered the castle to be put beyond the use of the English, out of reverence to this royal saint. Bruce’s son, David II rebuilt the castle following the end of the Wars of Independence. Between 1368-77 David’s Tower was among the first of a new form of tower-house castle then being built in Scotland. The three-storey, L-plan tower house was one of a number of stone towers built and was the principle Royal residence. It was enlarged in the 15th century but was replaced as the main lodgings in the 16th century by the Palace. The tower was largely destroyed during the 1571-3 Lang Siege. It remains were entombed within the Half-Moon Battery until they were rediscovered and excavated 1911-12.

Renaissance and royalty to a military fortress

During the 1400s, Europe entered a period known as the Renaissance, a great flourishing of new ideas in the arts, architecture, philosophy and fashion. Its influence was soon embraced by Scottish Monarchs.

This desire was partly expressed in costly building schemes at Scotland’s royal residences such as the Royal Palace on the east side of Crown Square. This began as an extension for David’s Tower in the 1430s, and was further enlarged to become the royal residence itself. There is little left of the original building, the King’s Great Chamber built for James I in 1434-5. However this was completed by James IV in the early 1500s, with the completion of Crown Square as a quadrangle enclosed on all four sides. Its buildings were grand to reflect the majesty of his kingship.

James’s confident knowledge of the Northern Renaissance is reflected in the carved corbels of his great Hall. The Great Hall, was built in 1509–11 for James IV to host lavish banquets and state events, continuing the grand courtyard project started by his father James III. Its hammer-beam roof is one of only two surviving late-medieval roofs in Scotland.

Towards the middle of the 16th century the Royal family were spending more time at the other end of the Royal Mile in the Palace of Holyrood where James V had carried out extensive building works. From this point on Edinburgh Castle took on the role as a fortress rather than a Royal residence, with it being used for ceremonial functions and exceptional circumstances such as the birth of James VI in 1566.

Castle under siege

Welcome to the most besieged place in Britain. We know of at least 26 separate occasions when an attempt was made to take it, either by force or covertly. Surprisingly for a castle that had such formidable defences, most sieges were successful. Often this was because the defenders suffered from disease, shortage of military arsenal or – crucially- lack of food and water. As an elevated site, the castle relied on wells, for water supply. When these were clogged, sabotaged or poisoned, the defenders were forced to surrender or die.

In 1544 the castle survived an attempt by English forces to capture it, and despite holding out, it was decided to strengthen the defences and weaponry of the castle as they were largely unchanged since the 14th century. In the late 1540s the Forewell Battery was constructed and a gun hole inserted in David’s Tower.

Another upgrading of the Castle defences was undertaken again in the late 17th century, designed by Captain John Slezer. This included Foog’s Gate, Dury’s Battery, Butts Battery, and walling below the Queen Anne Building.

Next time…

Catch up with us next week when we’ll track the changes that took place at Edinburgh Castle through the 18th century to the present day. Sign up for our newsletter to get blog updates straight to your inbox.