Pirates of Edinburgh Castle

2 December 2025

Craig Kerr from the castle guiding team uncovers the story of the pirates of Edinburgh Castle.

The story of Edinburgh Castle tends to focus on royal and military history but there are other stories to uncover. The final chapter of two men kept in the prisons is a story worth telling, for these men were not just petty criminals locked up for minor offences.

These men were real pirates of the Caribbean.

The idea of pirates of the Caribbean within Edinburgh Castle may sound strange, but it’s true. These pirates were indeed imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle towards the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Of these pirates, two, John Clark and John Stewart, served as guests of His Majesty, George I. In the winter of 1720/21, both pirates’ stories ended with a quick drop and a sudden stop. With their last breaths they were able to tell the people of Edinburgh the stories of how they sailed under the black flag and tragically wound up at the gallows.

The prisons in Edinburgh Castle where the pirates were held.

The defiant pirate John Clark

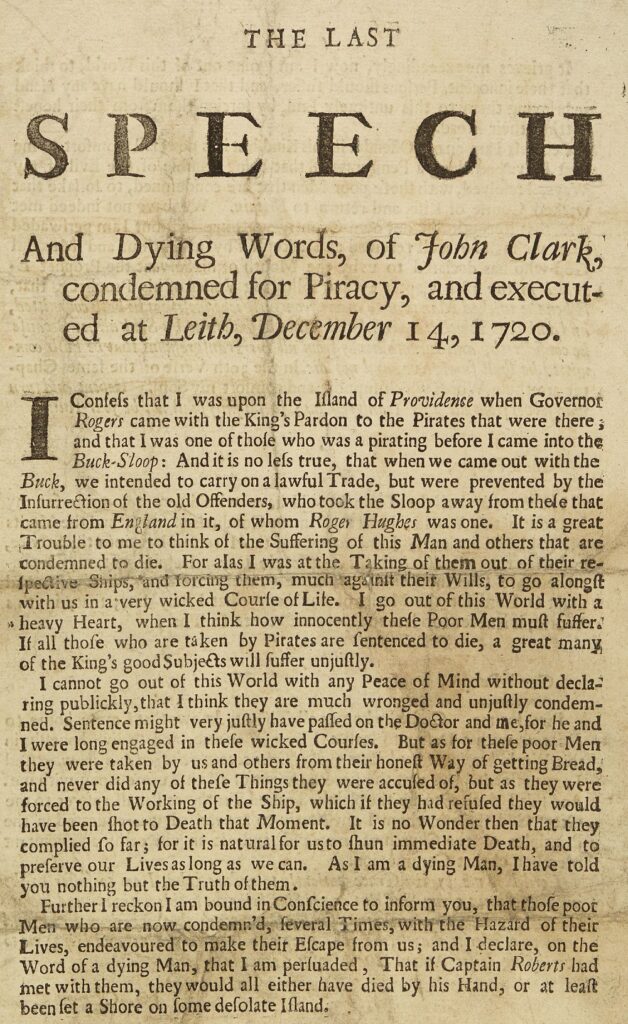

“I confess that I was upon the Island of Providence when Governor Rogers came with the King’s Pardon to the pirates that were there; and that I came into the Buck-Sloop.”

(The Last Speech and dying words of John Clark, condemned for Piracy, and executed at Leith, December 14, 1720.)

Clark was in Nassau on the island of New Providence on 24 July 1718 when Governor Woodes Rogers arrived with a surprising offer. King George I and the British Parliament thought they had a solution to the Caribbean’s pirate problem: offering the pirates forgiveness for their crimes. Could this deal give the pirates a way out of their lives of crime?

Piracy in the Caribbean increased after Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713). The conflict took place in North America and involved the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain. During this time, many individuals enlisted to raid Spanish treasure fleets. They hoped to claim a share of the valuable cargo.

These sailors were called privateers. Privateers were basically pirates with a country’s permission to attack the ships of enemy nations. When the war was over these sailors found themselves out of a job, so many decided to just take a further step into piracy. They would sail under their own flags and answer to no kings or governments.

Double-crossing blaggards

Upon the government’s arrival in Nassau, Clark took the pardon. Governor Rogers, as a sign of good faith, entrusted Clark and other pardoned pirates with a mission to inform the governor of Cuba that Rogers was going to resolve the pirate problem permanently. However, Clark and his fellow “reformed” pirates mutinied and stole the “Buck” and sailed to Africa.

The “Buck” soon came under the command of the infamous Welsh pirate Howell Davies. Its crew raided and pillaged across the west coast of Africa. They soon realised that more skilled crewmembers were needed.

Clark chose the pirate life, like many others who were searching for a better future. However, in his execution speech, he admitted to forcing others into piracy. We don’t know how many were coerced, but two names stand out. One was John Stewart, who shared a cell with Clark in Edinburgh Castle. The other was the notorious pirate captain, “Black Bart” Roberts.

The last speech and dying words of John Clark. Credit: National Library of Scotland. License: CC-BY-NC-SA

The tragic pirate John Stewart

“And I do solemnly declare as a dying man, that whatever I did while I was aboard of the pirate ship, was by force, and upon the peril of my life.”

(Broadside Regarding the Execution of John Stewart, January 4, 1721.)

Stewart seemed to have had a more honest background in sailing than Clark. In his own words he told the people of Edinburgh that he had sailed from Dartmouth, England, on 28 March 1719 on a ship called the “Mark de Campo”. They arrived at the coast of Guinea on 2 June, where Captain Howell Davies presented him with a simple choice: join or die.

Captain Howell Davies would not enjoy the company of his new crewmembers for long, though. Davies was killed by the Portuguese less than three weeks later, on 19 June at Principe. One of the new crewmembers, the notorious “Black Bart” Roberts, was voted in as captain. Though forced into it, Roberts accepted his new role because, as he stated during his inauguration, “tis better to be a commander than a common man.” Captain Roberts would launch a reign of terror throughout the Atlantic Ocean that had never been matched.

The tide turns against “Black Bart” Roberts

Stewart, along with Clark and forty other crewmembers, grew tired of Robert’s captaincy. After they captured the “Sagrada Familia,” the wealthiest ship in a Portuguese fleet off the coast of Brazil in May 1720, they betrayed their new captain. They stole Robert’s ship, the “Royal Rover”, and elected Captain Walter Kennedy. The pirates had their share of the treasure (including jewels that were meant to be sent to the Portuguese King) and took one last ship, the “Eagle” for themselves off the coast of Barbados. It seems there truly was no honour among thieves!

Stewart might have been telling the truth when he said that he wanted to escape a life of piracy. The “Eagle” theft was intended to be a passage to freedom. The pirates wanted to sail to Ireland to live out the rest of their lives as rich men. But, unlike Roberts, Kennedy was not a navigator, and they ended up on the west coast of Scotland. Twenty-one crewmembers were arrested in Argyll and were subsequently transported to Edinburgh Castle where a dozen of them would be executed.

“A merry life and a short one”- “Black Bart” Roberts

Both Clark and Stewart would meet the same fate despite living the pirate lifestyle differently. Clark confessed his crimes immediately and was hanged in Leith on 14 December 1720, whereas Stewart pled his innocence until the very end. He followed Clark barely a month later 4 January 1721 after a brief stay in the prisons of Edinburgh Castle.

Pirates’ lives tended to be short as the British authorities rapidly hunted many of them down. The treacherous Captain Walter Kennedy followed his former crewmates in July of 1721. He lost his fortune to gambling in Dublin and was later recognised by a merchant sailor in London.

The merriness and shortness of life was best understood by Captain Roberts. He too was hunted down and killed by the Royal Navy off the coast of modern-day Gabon on 22 February 1722. With the death of the most successful Caribbean pirate captain in history, the Golden Age of Piracy came to an end.

An image of Bartholomew Roberts from A General History of the Pyrates. Engraved by Benjamin Cole (1695–1766), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Dead men tell no tales, but one yet to be born will

“As I was waiting, a man came out of a side room, and, at a glance, I was sure he must be Long John”

(Treasure Island, Robert Louis Stevenson, 1883.)

The stories of John Clark and John Stewart ended at Leith Sands over three hundred years ago. Their lives have almost fallen into obscurity. However, one of Edinburgh’s most famous authors, Robert Louis Stevenson, would subsequently write the novel that ignited our love for Caribbean pirates and created our modern idea of piracy: Treasure Island.

Growing up in Victorian Edinburgh, Stevenson would have seen Edinburgh Castle above the city he called home for many years. Whether he knew the stories of John Clark and John Stewart is up for debate. But he created the most famous pirate John of all: the legendary Long John Silver.

It seems only appropriate that we honour Stevenson’s memory with a monument here in Edinburgh. This serves also as a small tribute to Clark and Stewart, because since the monument stands in Princes Street Gardens, it is in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, where those very pirates where once held as prisoners.

© Crown Copyright: HES. Take a closer look on trove.scot